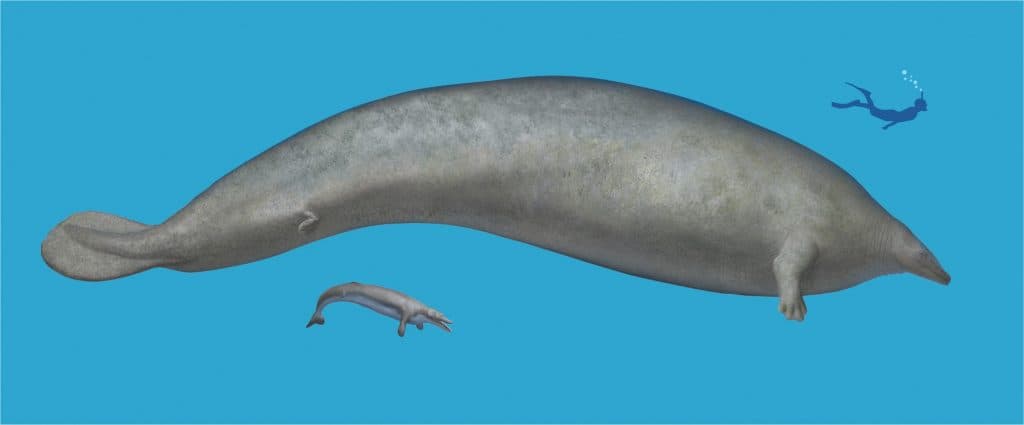

Move over, the blue whale. There is a new contender for the title of the most massive animal in Earth’s history. Scientists on Wednesday described fossils of an ancient whale unearthed in Peru that may have dethroned the long-reigning behemoth. The specimen, called Perucetus colossus, lived about 38-40 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. It was a creature built somewhat like a manatee but much more significant. The researchers estimate it weighed between 85 and 340 tons. That would put it well above the current record-holder, the blue whale, which weighs an average of 180 tons.

The fossils were excavated in the coastal desert of southern Peru, a region renowned for its wealth of cetacean (whale, dolphin, and porpoises) bones. Researchers carefully removed 13 vertebrae, four ribs, and one hip bone from the giant creature. Its bones were unusually dense and compact, a trait known as pachyosteosclerosis. It is rare in living cetaceans but found in sirenians, including dugongs and manatees. It took years and multiple trips to collect and prepare the fossils and even longer for scientists to confirm they had uncovered something remarkable. It turns out to be a new species of basilosaurid, an extinct family that resembled small deer but adapted to life in the water. The discovery suggests that the basilosaurids peaked in body size 30 million years earlier than previously thought.

In addition to being the heaviest cetacean ever recorded, Perucetus colossus is the largest ever known marine mammal and the most prominent four-legged vertebrate of all time. The researchers say that its colossal size and the era in which it lived open the door to many questions about prehistoric life.

“The main feature of this animal is certainly its extreme weight, which shows that evolution can generate organisms with characteristics that exceed the limits of our imagination,” said Giovanni Bianucci of Italy’s University of Pisa, lead author of a study published in Nature. Researchers calculated that the Perucetus colossus had an average mass of 180 tons from the fossil bones discovered in the Ica desert. The minimum mass was about 85 tons. The heaviest blue whale weighed around 190 tons, though it was longer than Perucetus at 110 feet (33.5 meters).

The skeleton also suggests that Perucetus colossus acted as a scavenger in shallow seas, taking advantage of the abundance of dead vertebrates there. The awe-inspiring specimen and other discoveries from the same geologic period in Peru provide clues about how cetaceans evolved into their modern forms. The fossils help show how the cetaceans adapted to an entirely aquatic lifestyle. They are also shedding light on the ancient world of the seas, which was far more productive and diverse than is generally appreciated. “This is a window into the deep seas of the past,” says one expert not involved in the study. “It is a very fascinating time for paleontology.” NBC News’ Hans Thewissen contributed to this report.