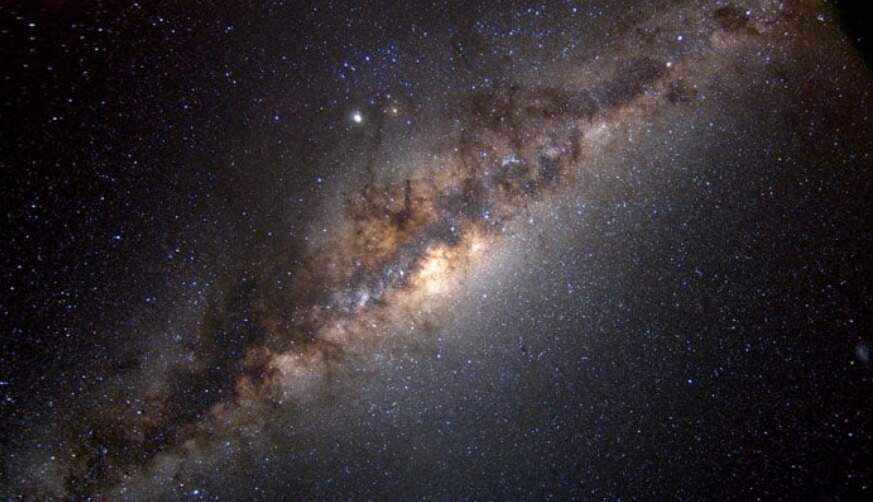

For decades, scientists have searched the skies for signs of aliens in various iterations of SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence). Unfortunately, no such evidence has emerged aside from occasional blips on the radar. But a new effort is expanding the search to monitor a star-dense region toward the core of our galaxy. This area could be an ideal spot for aliens to broadcast signals to kick off the interstellar conversation.

As astronomers have learned more about our galaxy, some have wondered whether civilizations elsewhere might be more advanced than we are. Some of the most intriguing speculations focus on technologies that may allow such civilizations to communicate across vast distances of space. For example, an alien able to harness the energy of stars and planets around them may transmit radio signals far more potent than those generated by Earth. Such transmissions, known as technosignatures, would be much easier to detect than the electromagnetic waves produced by our technology.

Some researchers have tried to find technosignatures by searching the atmospheres of planets for chemical pollutants, such as nitrogen dioxide gas produced by industrial activity. Others have looked for traces of the massive construction projects of intelligent civilizations, sometimes called megastructures. These would be harder to miss than a single transmitter sent by an alien civilization but would require much more sophisticated technology.

Earlier attempts to detect alien technological signatures have focused on a narrowband radio signal type concentrated in a limited frequency range or on single unusual transmissions such as the Arecibo message sent into the globular star cluster M13 in 1974. But a recent paper in the journal Science Advances describes a search initiative, co-funded by Cornell University, the SETI Institute research organization, and Breakthrough Listen, that is much wider and more encompassing. The new BLIPSS project is now monitoring a star-dense region toward the galactic center with many times more potential habitable exoplanet systems than previously targeted areas.

The team’s new effort focuses on a specific class of periodic spectral signals that might be the technosignatures that intelligent aliens rely on. First, the astronomers use data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope, surveying more than 1.1 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy. Then, they divide the sky into small swaths and look for those that might contain such technosignatures using statistics, data analysis, and machine learning techniques.

The astronomers aim to look for a techno signature called “eclipsing periodic spectral signals.” These signals repeat over time and are similar in shape to radar pulses. They hope to detect the signals in a wide range of frequencies and refer any anomalies found to ground-based telescopes for more dedicated searches, including radio SETI searches. The study is an example of the potential for software to be a powerful science multiplier for search efforts. It shows that we can target the most promising areas of our galaxy for a more focused approach to detecting technosignatures and expand the chance that we will hear a response from another civilization.